|

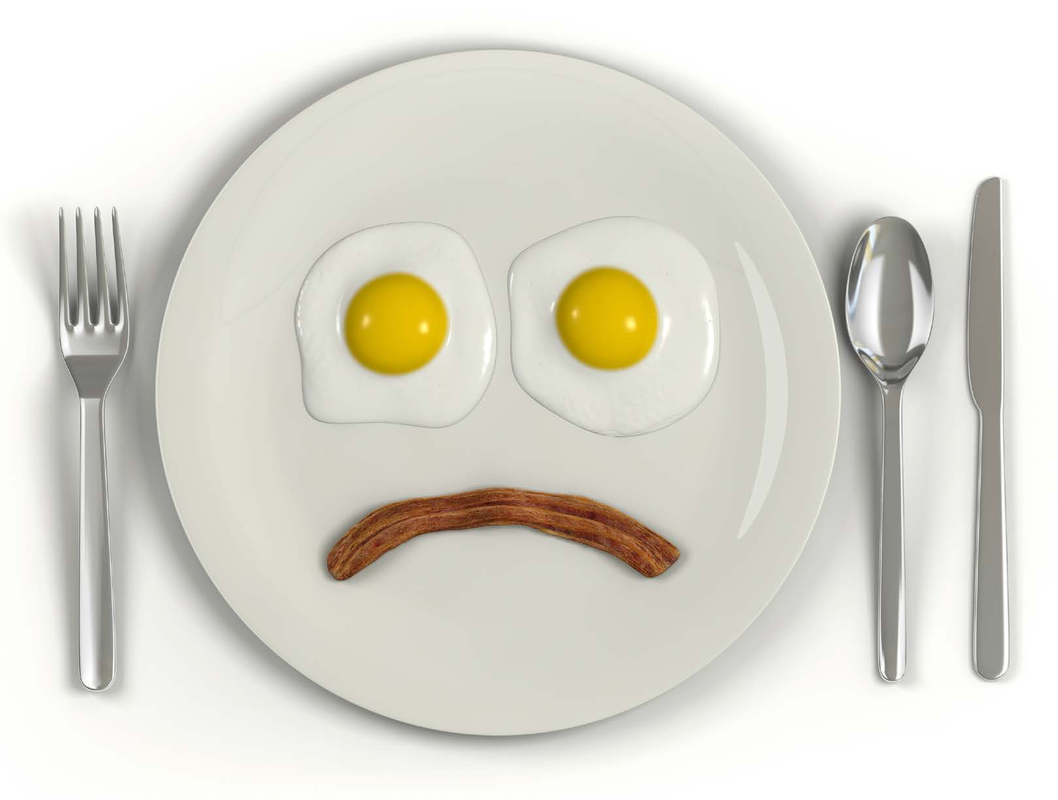

Many scientific studies either proclaim a particular food will kill you or help you live to be 300 years old, said Harvey Levenstein, professor emeritus of history at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada. “It starts with some kind of a warning and it sounds like it’s very, very certain, but then by the time you get to the third or fourth sentence, then the ‘may’ becomes the operative word … but people don’t read it that way. They just read the headline: ‘X Food Will Kill You, Say the Experts.’” Food producers with a vested interest will often claim food is healthy. It’s up to individuals to determine the value of the foods they eat. Take, for example, Time magazine, a weekly publication that reported a circulation of more than 3 million in 2013. In March 1984, the magazine’s cover featured a paper plate with two sunny-side-up eggs for eyes and a slice of bacon as a frown. “Cholesterol” was in bold, yellow letters; below, the words “And Now the Bad News …” appeared. Thirty years later, a curled shaving of butter appeared on Time’s cover beneath the headline “Eat Butter. Scientists Labeled Fat the Enemy. Why They Were Wrong.” In the span of three decades, the magazine had characterized saturated fat as both villain and savior. Such labels are problematic, said Jean-Marc Schwarz, a professor and researcher in the College of Osteopathic Medicine at Touro University in California. “Science is much more nuanced than black and white,” he explained. “People want one list for foods to eat and another for what not to eat. And it’s just more complicated than that.” There Is No List. Banning foods from your diet leads to disordered eating habits, said Brian St. Pierre, director of performance nutrition at Canada based nutrition-coaching company Precision Nutrition. Nutrition questions seldom have black-and-white answers, leaving many people confused. The best approach involves tracking intake and evaluating the results, then optimizing your diet. “Eating one slice of pie or even eating something high in trans fat one time is not going to make or break anything,” he said. “One meal out of 28 is a small portion of your intake, and it’s just one piece of the meal. It’s not like you’re eating the whole pie.” St. Pierre added: “It’s the things you do consistently that ultimately determine your health, your body composition or your performance.” Almost every food, if consumed in excess, can lead to negative effects, Schwarz noted. “Water is toxic if you drink a lot of it,” he said, referencing hyponatremia, a condition in which a person’s lungs and brain become flooded from drinking too much fluid. “If you drink a lot of water, you can kill yourself.” The same can be said for cyanide. The poison is found in such small amounts in cherry pits and apple seeds that eating the fruits in typical quantities poses no real threat. Eat about 20 apples—seeds included—in one sitting, however, and the results could be deadly. Dietary fat is no different. While fat doesn’t make you fat, overeating anything will. Plus, there is no one thing called “dietary fat.” There are seven types of dietary fat; some are good, some are not so good. “So a low-carb diet is a very, very good diet in the long term, but if you’re on a super high-fat diet, it’s not necessarily a good thing,” explained Dr. Richard Johnson, professor of renal diseases and hypertension at the University of ColoradoDenver’s Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora. “Depends on what kind of fat. … Not all fats are equal.” For that matter, not all carbs are created equal either, added Johnson, author of “The Fat Switch.” “Vegetables have a lot of carbohydrate but are really very healthy. But pasta and bread may not be as healthy.” It’s enough to cause analysis paralysis. “Overall, everyone wants to avoid death and illness,” Levenstein noted. And food is the medicine that can delay or prevent both. “It’s gone haywire over the past decades because you’ve got a whole series of people with interest in convincing you that certain foods are either good or bad for you,” continued Levenstein, author of “Fear of Food: A History of Why We Worry About What We Eat.” “On one hand you have all the food producers who’ve latched onto the notion that you can use these scientific studies that supposedly show that their food is good for you … but I guess you can start with the people who produce the scientific studies, who have an interest in their professions, who want research grants and so forth, who come to … firm conclusions about the relationship between food and health.” CrossFit’s advice: Track the numbers. Just like you collect data on workouts, collect data on diet. If a particular food doesn’t improve health and performance, eliminate it. Levenstein’s advice: Be skeptical. “The things they told you are bad for you in the past now are good for you, and it’s going to continue like this,” he said. “We’re always going to be bombarded by people … trying to scare us into buying their things or following their advice. There’s too much money to be made … for it to stop.” About the Author

Andréa Maria Cecil is assistant managing editor and head writer of the CrossFit Journal.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCrossFit Pretoria Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed